Riser height and tread (going) form the rise-to-going ratio — the foundation of comfort, safety, and standards compliance for any staircase.

See how fast it worksRiser height and tread (going) are the most conspicuous dimensions on a stair and essentially the basis of any assessment. Their relationship is called the rise-to-going ratio and is stated in cm, e.g., 18.6 / 26.

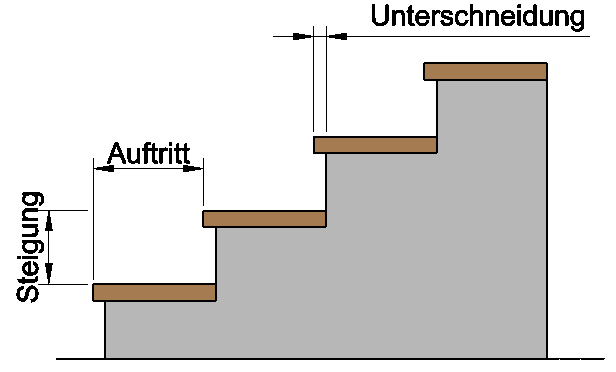

First, some terminology — a picture says more than a thousand words.

The riser height is the vertical distance between the treads of two consecutive steps. The value results from the range permitted by the standard and from applying the step-length rule. Values above 190 mm are generally perceived as too high locally.

Where space is tight, slightly increasing the riser height to reduce the number of rises can enlarge the tread (going). Especially when descending, a small going is hazardous, whereas a larger riser is merely a bit more strenuous.

Riser height is usually determined first as follows: divide the floor-to-floor height by the estimated number of rises and adjust the number of rises until the riser height is in the desired range.

n … number of rises (not treads!)

H … floor-to-floor height

630 … optimal step length [mm]

a … tread (going)

The tread (going) is measured as the shortest distance between the intersections of the walking line with two consecutive nosings, viewed in plan. If the walking line is an arc, this is the chord. The going therefore has nothing to do with the overall tread width.

As with riser height, the value comes from the standard’s range and the step-length rule. For straight stairs, the going can also be derived from the walking-line length.

l … walking-line length

n … number of treads

630 … optimal step length [mm]

s … riser height

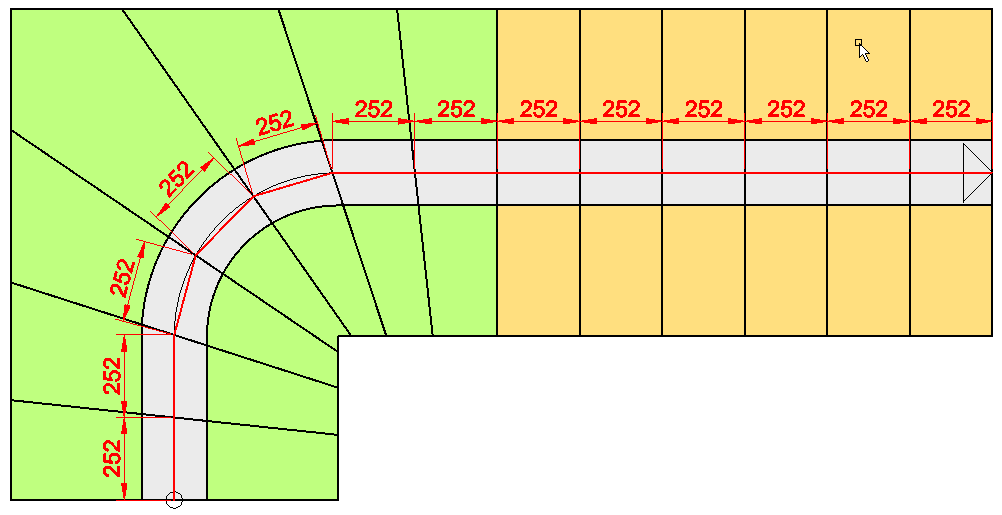

With winder stairs whose outer dimensions are fixed, the following occurs: the walking line is set and drawn into the plan. The walking line must then be subdivided into goings — as chords along the curved segment.

This is (to my knowledge) only solvable iteratively numerically, and graphically by trial: choose an estimated going, step it off with a compass along the walking line to the end, check if the remainder is long or short, then repeat with a corrected value. Ultimately you only converge approximately on the correct value.

A generic CAD program doesn’t help much here; I’m not aware of one that splits a polyline into a desired number of equal chords. CAD users will estimate the going as precisely as possible, step it off with circles (save your screen from the real compass), and then tweak the last step or overall length.

Nosing overlap is the “overhang” of one tread over the next riser. For all open stairs (those you can see through from the front), provide at least 30 mm of overlap.

This is often overlooked on escape stairs with grating treads, due to confusion with industrial stair rules where only 10 mm may be required.

Special rule: For required stairs with goings under 260 mm, going plus nosing overlap must total at least 260 mm.

Spiral stairs often use prefabricated treads that do not yield parallel edges once installed, so overlap varies along the edge. Determining overlap at the walking line is likely in the spirit of the standards.

s … riser height

a … tread (going)

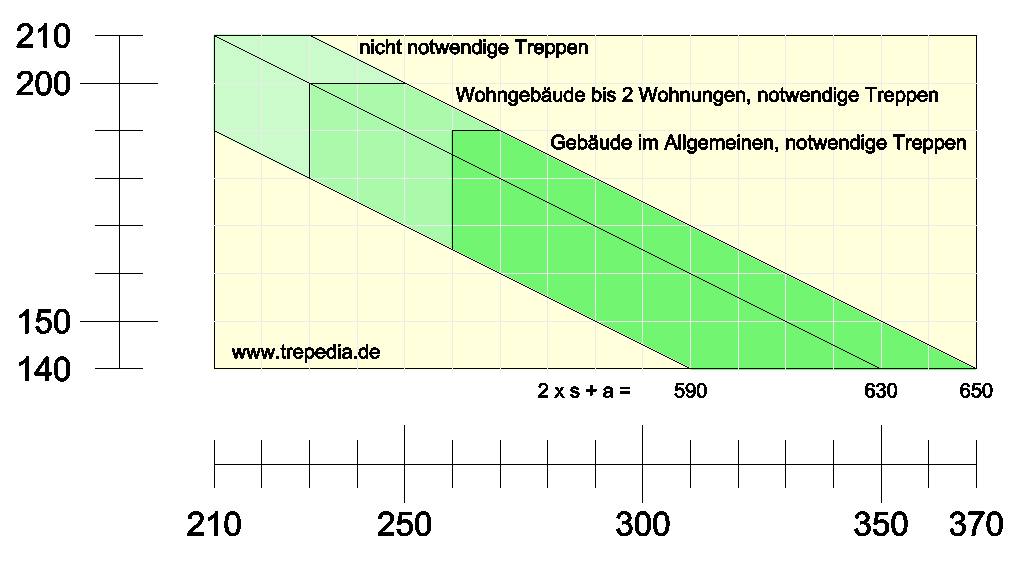

• DIN 18065: 590–650 mm

• EN 14122-3: 600–660 mm

• Target: aim for ~630 mm

The step-length rule approximates an adult’s stride on stairs. The formula and ideal value date to the 16th century, when average stature was likely smaller.

Whether they should still apply unchanged is debatable; in German-speaking countries they are commonly used. Other countries differ — for example, the Netherlands often builds steeper, more compact stairs even when space allows.

There are proposals to modernize the rule. A so-called sine formula aims to improve walkability for very shallow or very steep stairs, but it has not entered official standards yet.

I once visualized the DIN 18065 ranges for going, riser, and step length in a single chart. You can play with values without constant recalculation — and print it directly as a PDF.

a … tread (going)

s … riser height

The comfort rule aims to minimize effort when walking stairs. It is not specified in the standards, which is reasonable given the limited evidence, but it is still often cited in stair design basics.

a … tread (going)

s … riser height

Adhering to the safety rule is intended to reduce accident risk when climbing stairs. Like the comfort rule, it is not mentioned in the standards and the evidence is limited.